Photo Essay: Raising the Gods

- iconsofkemet

- Sep 4, 2021

- 4 min read

NOTE: This feature was originally posted to the Icons of Kemet BLOGGER blog on Monday, March 2, 2015, and titled "Photo Essay: Raising Hwt-Her (Hathor) Mistress of the Sky."

The ancient Egyptians achieved the miraculous in the decoration of their temples and monuments, sculpting hard stone into the softest, most delicate of forms in order to breathe life into the places where gods and kings would tread. When I say "decoration", I must be careful not to evoke the concept of art for art's sake, or ornamentation strictly for aesthetic considerations; as these concepts did not exist in ancient Egypt. What we call decoration of Egyptian temples and monuments was in fact carefully orchestrated magical composition, images whose purpose was to actively engage in the sacred work of maintaining creation and the cosmic order. Art works in ancient Egypt were animate creations to their makers, part of a highly ordered program of ritual activities that comprised what academics call the cult of Egyptian religion. Cult in ancient Egyptian religion is the entire corpus of sacred activities, ranging from ritual offerings and gestures to two and three-dimensional deity images. It was the deity image or cult image that formed the backbone of the temple system in ancient Egypt(1).

Three-dimensional cult statues made of solid gold and inlaid with lapis lazuli and other costly stones were maintained in every temple complex in Egypt, and these were the focal point of the elaborate rituals of the daily cult. However, such images were only one type of deity image to be housed in the sacred precincts. Still to be seen today in temples throughout Egypt, though far from the brightly painted glory of their heydays, are the astonishing range of both low and high relief carvings that covered literally every inch of these sanctuaries. The Egyptians specialized in bas-relief, the very laborious and time-consuming technique of cutting down all the background stone of an image in order to leave it raised up slightly from the surface. Such sculptural details were used throughout Egyptian temples to highlight important ritual images of the king as high priest performing the activities of the temple cult.

Images of the Gods, too, were central to the elaborately sculpted and painted bas-relief programs added to magically awaken Egyptian temples, and there is plenty of evidence to show that certain of these images became focal points for cults of their own(2). The most hallowed interior spaces of Egyptian temples were accessible only to special classes of the priesthood, however, the outermost walls of temples were places where common Egyptians could congregate in order to approach the Gods through special images carved into the stone surfaces of the temple(3). Archaeological evidence amply supports the existence of sacred spaces for public and/ or semi-private prayer and worship that existed on the outer, public walls of Egyptian temples. These existed in the form of relief images that were regarded as especially sacred, and were sheltered by cloth enclosures suspended from wooden dowels fitted into holes drilled into the stone around the images(4). Some such images were even inlaid with colored and highly reflective materials in order to highlight their sacredness. Such spaces provided a semi-private means for ordinary Egyptians to give their personal petitions to the Gods.

My own work as a Kemetic iconographer strives to build a bridge between traditional and ancient avenues for worshiping the netjeru (Gods), and contemporary needs and considerations. We no longer have the vast resources of a state-supported religious system to maintain our temple traditions, and the temples themselves have radically changed in stature. We are groups of devotees here and there, many on the Internet, doing our very best with often considerably limited means, to carry on a millenniums-old tradition of honoring Egypt's original deities. My strongest means of accomplishing this is through the revival of the cult image as a means for establishing an authentic energetic link with the netjeru, which forms a foundation for the practice of the daily cult.

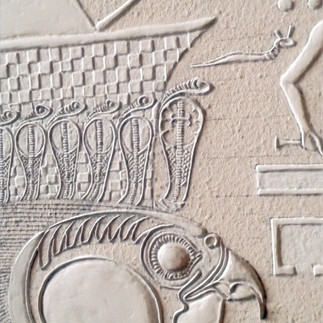

I am obviously not working in stone, thus true bas-reliefs are not my medium. However, I have developed my own technique for continuing the time-honored use of raised relief surfaces for sacred images of the netjeru. Using gesso in a liquid form, I carefully build up especially significant details of my icons into 'bas-reliefs', which are then gilded with 22 karat gold. Crowns, jewelry, hieroglyphs, and certain parts of a deity's anatomy are prime candidates for gilt relief treatment in my icons. These portions of the icon will then stand out considerably in the shrine and ritual environment, where they will be viewed primarily by candle light. Real gold has always been used for icons in many iconographic traditions around the world, and this because gold is not only a precious commodity, but also because of its luster when exposed to direct or indirect lighting. This effect is significantly heightened when the thinest leaves of gold are layered over a finely detailed relief surface.

A similar effect was achieved by the artisans who crafted the miniature gold-covered shrine found in the 18th Dynasty tomb of Tutankhamun. In this instance, craftsmen used a linen-covered plaster base in order to produce very delicate raised reliefs, which were covered in thick sheets of gold foil that were then exquisitely chased(5). My technique may be somewhat different, but it is completely in keeping with the spirit of such ancient works recovered from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Instead of working my details into thick sheets of gold foil, my technique uses a liquid gesso to create raised and intricately detailed surfaces to receive the thinest and finest gold leaf available.

Notes

1) Teeter, Emily. Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. New York, NY, 2011, pp. 41-46.

2) Ibid, pp. 78-83.

3) Ibid, p. 83.

4) Ibid, p. 78.

5) Reeves, Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. New York, NY, 1990, pp. 140-141.

I now present a collection of photographs of multiple icon panels which show my gesso reliefs prior to sealing with shellac and gilding.

Comments